It was in the spirit of the times. In the middle of the 19th century, industrialization was in full swing in England, disrupting the landscape, both physically and socially, creating a revolution in every sense of the word. The country was modernizing, innovating, producing, leading to the expansion of cities, especially in the North, and the creation of new social classes. Alongside the ancestral divide between the aristocracy and the rural world, two new communities were created: a middle class of entrepreneurs on the one hand, and a huge working class on the other. The relationship of close interdependence between these two new social strata was complicated, conflicting and the source of all the changes that were going to occur in the Europe of the 20th century.

And that’s when Mr. Titus Salt came in.

He was a typical example of a new entrepreneur who owed his success to his pugnacity, his field work and his inventiveness. His was the world of textiles, and more specifically wool, that Titus Salt learned his business alongside his father. They were based in Bradford, a small rural town in Yorkshire that became the wool capital of the world in record time. Spinning mills sprung up like mushrooms thanks to the natural resources of the region and the population growing exponentially. The working conditions had followed the same curve, but in a completely opposite pattern. The workers lived on top of each other in appallingly unhealthy conditions and life expectancy was so low that the figures are shameful.

Titus was a discreet man, not very comfortable in public, but remarkably perceptive and assumed a great sense of responsibility. When he moved with his family to the outskirts of the working class neighborhoods, he could not believe his eyes. He discovered the misery of those around who depended on men like him to survive in an environment that had nothing human anymore. He therefore decided to put his visionary sense of commerce towards humanitarian services desperately lacking in this era.

While in charge of wool purchases for the family business, he encountered bales of alpaca on the docks of the port of Liverpool, coming from Peru. No one wanted to buy them because the wool was too difficult to card. He was convinced otherwise and spent 18 months working with his collaborators to tame this material from which he felt he could produce a unique fabric. His intuition and hard work were rewarded beyond his expectations. The result was sumptuous, combining the brilliance of silk with the qualities of wool and, very quickly, it seduced the royal family and all the elites of the country. Fortune was within reach.

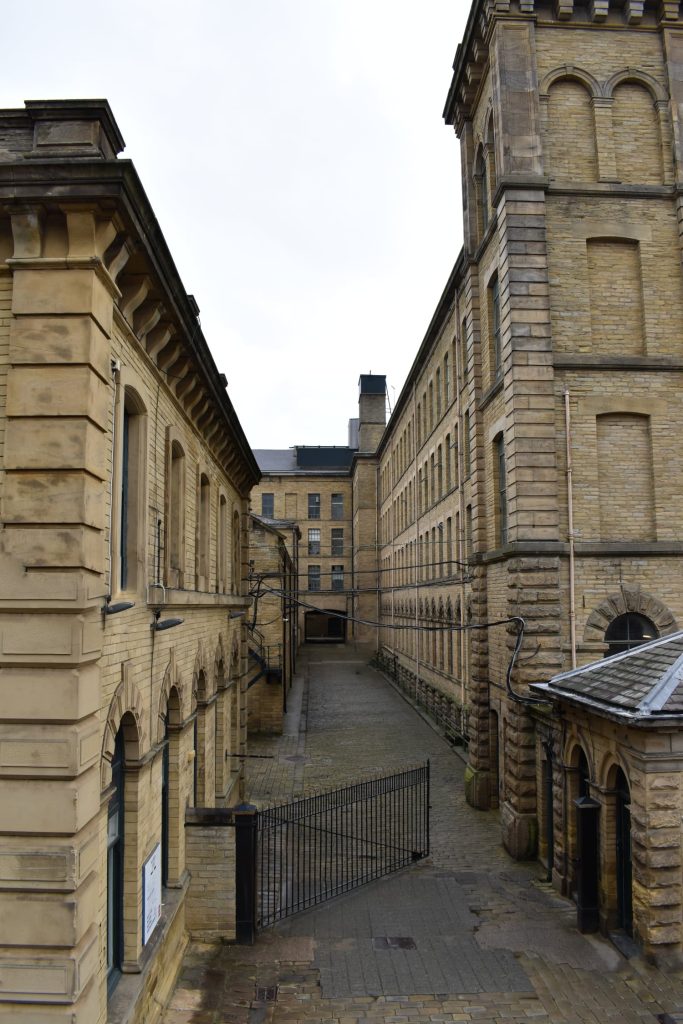

Titus Salt chose then to move his mills out of the unhealthy atmosphere of Bradford and, in 1851, acquired a piece of land a few miles from the city, strategically crossed by the railway line, the river and the canal that runs from Leeds to Liverpool. It was also a charming, bucolic and romantic place, qualities rarely associated with industrial exploitation.

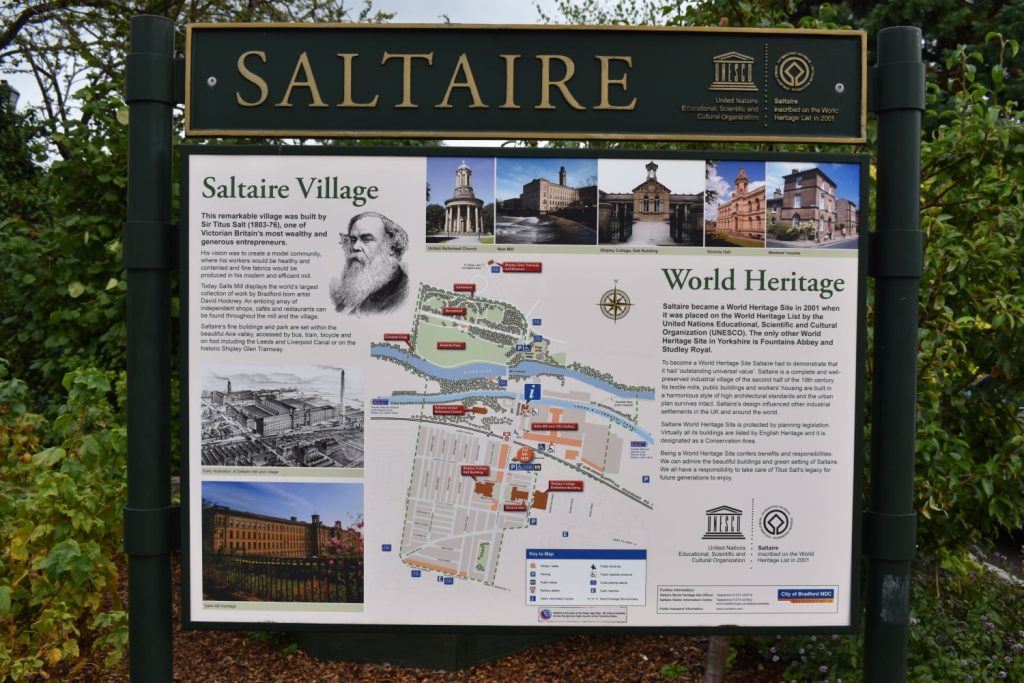

The tone was set! Mr. Salt and the river Aire “joined forces” to form the new town of Saltaire, in the center of which were built the spinning mill buildings and one of the world’s first workers’ towns.

Titus knew what he didn’t want anymore: drunken workers, sick with cholera, filthy, uncultured and depressed. His vision was as much philanthropic as it was productive, and he designed “his” city on human, social and aesthetic bases. No community palace like Godin* or utopian socialism like Robert Owen**, which were the other models of workers’ cities of the time. He commissioned two local architects, Francis Lockwood and William Mawson, to erect a city in a classical style inspired by the Italian Renaissance, using ashlar ( not brick as was customary in industrial cities).

The project lasted for 25 years. The 800 individual houses were particularly well cared for and comfortable, with a water supply, gas lighting and a garden, as well as separate rooms and a dedicated kitchen area – infinite luxury for these working class families compared to their past conditions! The streets were named after the first names of Mr. Salt’s children and the royal family and were organized around all the attributes of a city: two churches, a school, a theater, a hospital, public baths, retirement homes and a huge park. And the whole was harmonious, airy and aesthetic; it was then occupied by the 3500 people who worked for the Salt spinning mill!

Titus Salt believed in education for children, healthy living conditions, entertainment for all, care for the sick and the elderly. He was a political activist for better working conditions, shorter working hours and a city to live in, not just to house.

Even if his commitment was in the interest of the company, his humanism was not in doubt. He was a public man and a highly esteemed boss, as testified by the 100,000 people who followed his coffin at his burial in the Saltaire churchyard.

The Salt Mills industrial complex operated after his death with his descendants until 1986 and, as good ideas never get old, it was saved from abandonment by local businessman Jonathan Silver shortly thereafter.

The end of the 80’s was the beginning of another revolution: the restoration and reuse of monuments or industrial wastelands. This is how a new population came to live in Saltaire, mixing artists and new entrepreneurs of the digital world. Jonathan Silver has made his friend, Bradford-born artist David Hockney, a permanent guest at Salt Mills, and has dedicated the site to temporary exhibitions and to hosting digital companies. The site was listed by UNESCO in 2001.

Saltaire has escaped all demolition (only 1% of its heritage was destroyed) and has become the architectural jewel of its neighbor Bradford in the tourist and cultural development of the region. Much more than a testimony to the utopian workers’ towns of the time, it has succeeded in the risky challenge of being still inhabited, alive and active.

Sir Titus Salt was a visionary in both the manufacture of his alpaca cloth and in the design of a town. In both cases, he put human comfort and happiness at the center of his concerns!

Text from Claudia Gillet-Meyer and photos from Régis Meyer( unless two)

*Familistère de Guise built by Jean Baptiste Godin in 1859 (France)

** The village of New Lanark built by David Dale and Robert Owen in 1786 (Scotland)

MORE INFORMATIONS :

• SALTS MILL

• Sir Titus Salt, Baronet, His Life and Its Lessons, by Robert Balgarnie

https://librivox.org/sir-titus-salt-baronet-by-robert-balgarnie/

• Saltaire, ville-usine modèle du Nord de l’Angleterre : un objet urbain à part entière entre permanence et mutation par Aurore Caignet (IN FRENCH)

https://journals.openedition.org/rge/9253

• Saltaire, West Yorkshire, is a complete and well-preserved industrial village of the second half of the 19th century.