For a long time, he remained unknown or disregarded, probably because he did not display a modernity as radical as his student Le Corbusier. Facing the clear choice of his contemporaries to make a clean sweep of the past, Auguste Perret slowed down while being one of the greatest precursor architects of his time. A strange paradox. That could be seen, for example, in the question of the window, which Le Corbusier only wanted as a band in order to mark a break with the past, whereas Perret wanted it to be vertical, faithful to historical continuity.

Critics and the public do not like the “in-between” and this is precisely what Auguste Perret represented. A man between modernity and moderation. Today, fortunately, a new look is being taken at his achievements, particularly the city of Le Havre, his most colossal and emblematic project, classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005.

The first time I went through Le Havre, without really being able to linger, I found the city quite austere, even sad and monotonous.

The monotony of all its buildings which seemed to be very similar to each other disturbed me.

I was looking for the nooks and crannies in the straight lines, the chaos in the straightness, the life that comes from the disorder.

In fact, I had missed everything and especially the essential.

To discover Mr. Perret’s Le Havre, the eye must take its time and get used to the rhythm wanted by the architect, in order to seize the nuances like Ravel’s bolero.

Always the same and yet always different.

The history of this “new” city began in 1945 when the Ministry of Reconstruction and Urban Planning entrusted the Perret workshop with the task of rebuilding the city, which was then a huge field of ruins. 10,000 buildings had been destroyed during the war. Given the urgency, Perret was doubly the man for the situation, because he knew how to build in a modern style in an economical way. His workshop focused on the elaboration of a new city, without looking back to its past, by putting in place new urbanistic processes, a coherence in its overall plan and innovative and inexpensive manufacturing techniques thanks to the use of concrete, the master’s cherished material.

One can say that Monsieur Perret was literally in love with concrete. He not only used it for its immense stability and durability, he made it his architectural “order”. His experience in the workshop of his father, a stone cutter, taught him that a raw material can be cut, polished and sculpted. He believed, and rightly so, that concrete can also be worked.

“Concrete is the stone we make, much more beautiful and more noble than natural stone”.

Auguste Perret

He therefore plays with the composition of concrete, coating it to protect it, washing it to bring out its grain, bush hammering it to obtain irregularities in the surface, and dyeing it in the mass to change its shades.

In fact, Auguste Perret wanted to impose concrete as a supporting structure as well as a facing, but his contemporaries were not ready. He therefore began by making concessions with concrete constructions … covered with plated facades that contradicted his speeches. He did not have a free hand, whether it was in his building on the rue Franklin in Paris, his first important realization in 1903, which he covered with thin ceramic plates, or the new theater on the Champs-Élysées, eight years later, which he was forced to hide behind plates of white marble veined with gray, white and black.

Le Havre finally gave him the opportunity to show, on a large scale, all the possibilities of this material, without being ashamed of it.

In the housing units, intended for war victims, all social levels included, the Perret workshop designed apartments ranging from studios to F6, with unprecedented comfort for the time: double orientation, optimal sunlight, integrated kitchen and bathroom, garbage disposal, forced air collective heating. This feat was obviously possible thanks to the adoption of prefabrication, the systematic use of a modular framework, and the innovative exploitation of the potential of concrete.

Auguste Perret’s building style is based on two fundamental rules: the load-bearing structure (or framework) and the infill (walls). Each building was composed of beams spaced exactly 6.24 meters apart and the empty space was filled with concrete slabs that Perret adorned with all the subtlety of his shaping, varying the nuances and granularity of his material from one building to another.

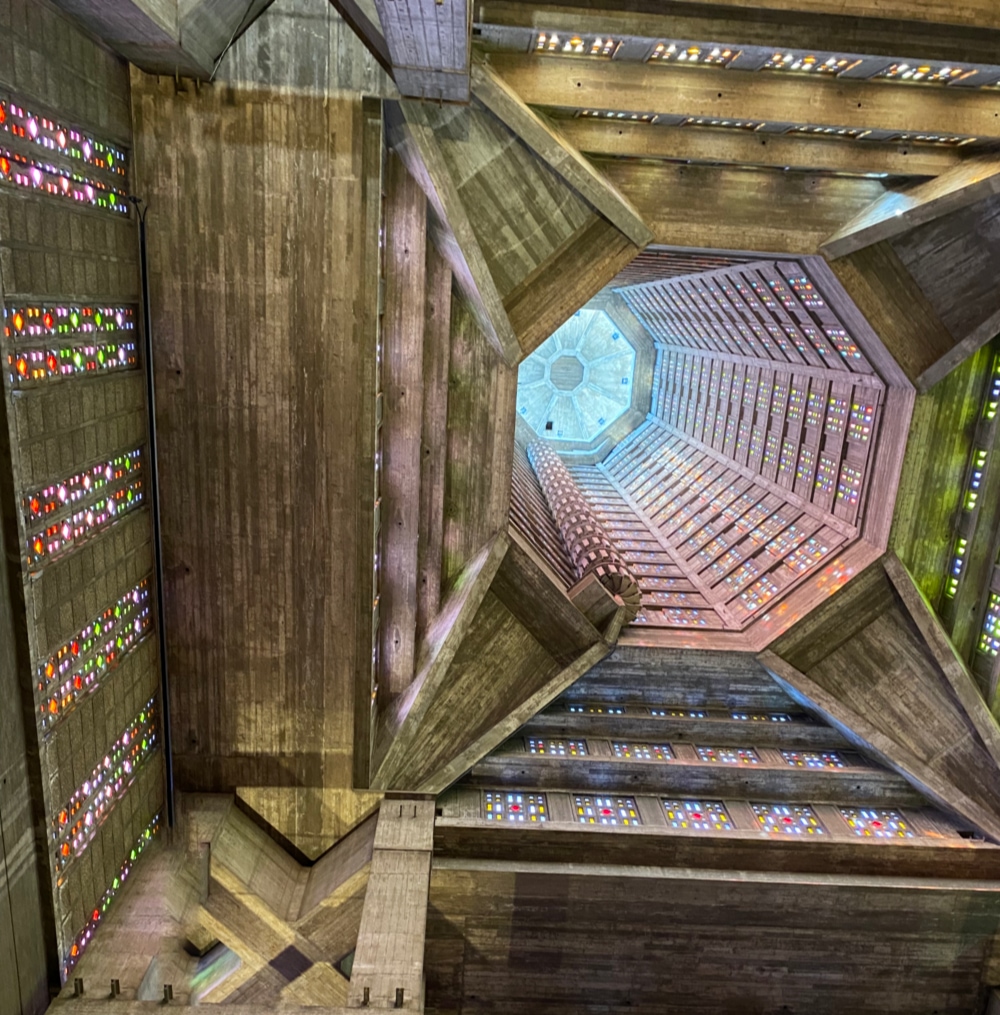

Certainly, Perret’s magic shines brightest in the realization of the church of Saint Joseph.

This all-concrete building, like the rest of the city, is incredibly elegant and light, thanks also to the luminous and shimmering stained glass windows by Marguerite Huré.

Auguste Perret never compromised on his convictions. He aligned with the builders. His ambition was different from that of his contemporaries because beauty, for him, was a moral requirement, a duty and a probity. He used to talk about “banality” in architecture as a will to conceive and realize what seems to have always existed. A “reasonable” architecture far from the competition of egos, no longer completely classical, without being completely modern, which would be the reflection of a calmed social vision.

Fortunately, after having disowned or misunderstood him, our contemporaries are finally paying tribute to him and his incredible achievements.

Text and photos : Claudia Gillet-Meyer