The art of private Chinese gardens reached its peak during the Ming and Qing periods (15th to 20th centuries) to the south of the Yellow River, particularly around the cities of Suzhou and Hangzhou. The lake located in the latter was often described as “paradise on earth”.

Private Chinese gardens were usually owned by scholars, and as part of their residences, were used to perform eremitism in an urban retreat.

Chinese gardens of the early modern period developed with a refinement and elegance very different to what was happening in Western landscape art at the same time.

The concept of “garden” in early modern China did not necessarily imply that plants were the focus of the landscape design. Scholar gardens were symbolic materialisation of a finite world in the infinite, a space where man can devote himself to his personal quest to perfect himself.

Picture the life of these Chinese scholars, as civil servants finally appointed to the imperial Court after passing long and tedious examinations. These cultured men put their talents at the service of the emperor, to guide and advise him and sometimes even criticize him. Ideally this was performed with humility and without flattery, amid a complex administration system and colleagues always ready to trip them up.

Their daily life was difficult, and they were always kept guessing how to remain honest and obedient while avoiding intrigues and traps. At times these civil servants might have to disobey if their morals came at odds with imperial decisions. Walking this tight rope, many scholars felt forced to resign or were punished and exiled for their opinions.

To survive the intense stress of their administrative job, many Chinese scholars built a garden for therapeutic purposes, as a place where they could find themselves and rebuild their inner peace.

At each period of Chinese history, Chinese gardens have been considered a haven and an escape from the hostile and corrupt world. In its design the Chinese garden exemplifies a microcosm within the macrocosm, where all the Taoist, Confucian and Buddhist traditions came together.

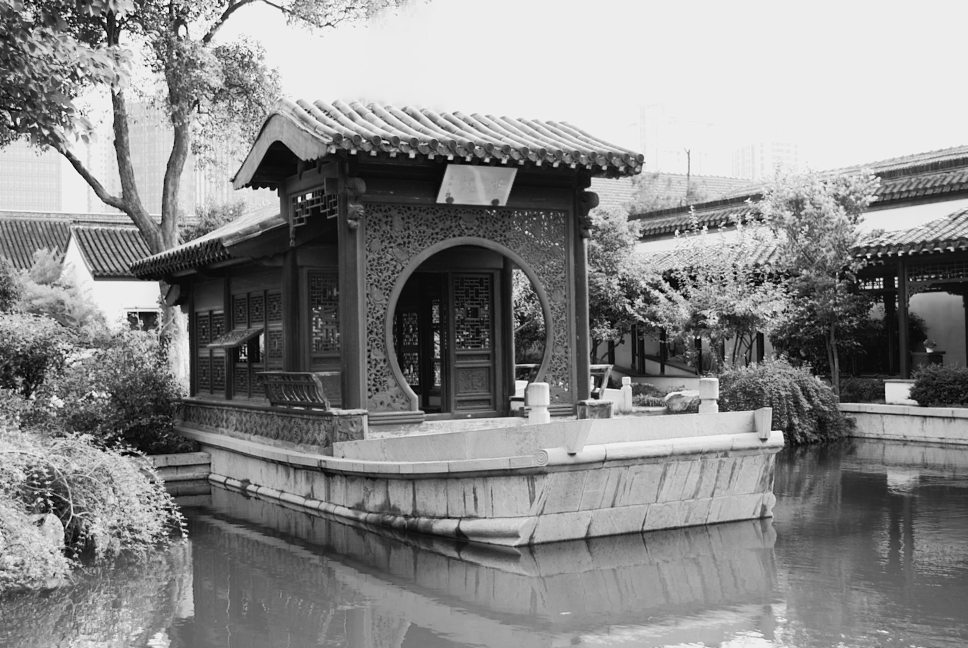

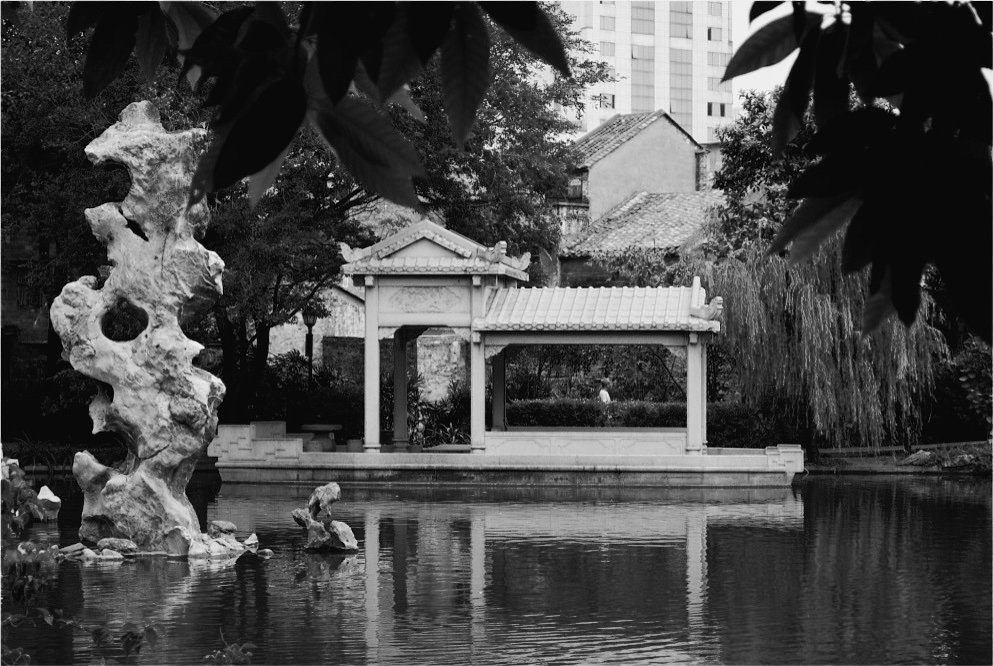

Another difference with Western gardens is that the Chinese garden is particularly anchored within architectural space, punctuated by various buildings, themselves connected by winding paths interspersed with half-moon or amphora doors. One wanders from kiosk to pavilion amid rockworks symbolizing larger mountains. Looking down one is usually rewarded with a waterscape populated with lotus and water lilies. Every part of the garden has a precise symbolic meaning, everything is coded. Nothing is left to hazard.

In this rather sophisticated context, there is one type of building that is more mysterious than the others. During my many visits inside Chinese gardens, I have found that this type of building was the most fascinating allegory of all.

“Suzhou Shizlin “

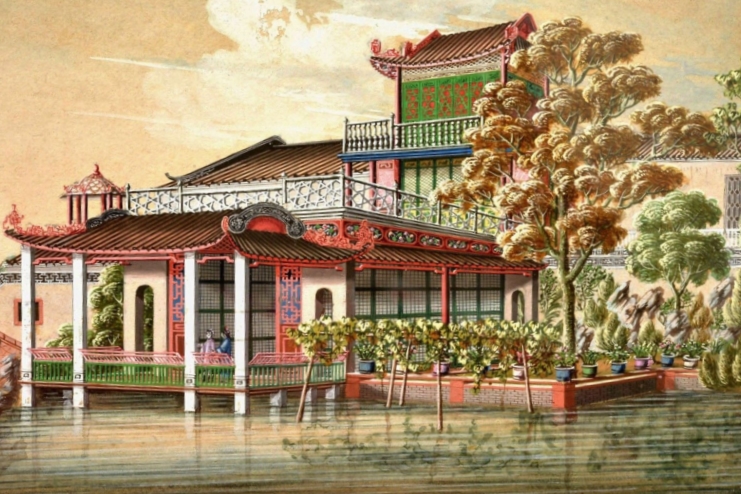

S on the edge of a pond, this building imitates the appearance of a boat, which is doomed to remain irretrievably docked. The first time I “climbed aboard” one of these curious boats, I was disoriented by the concept. For a long time, I remained leaning against the balustrade and my mind began to wander, charmed by the poetry of this structure and the irrepressible desire to travel that emanated from it. Unbeknownst to me, I began to feel the evocative power of this very special architecture.

This fake boat is named Fang in Chinese, often translated as “stone boat”, or “boat without moorings”. Some of these stone boats look more like a real boat than others, imitating the likeliness of traditional Chinese boats rather than what we might be used to in the West.

Where are these boats going? That is the implied question. A ship that cannot sail, built of stone and firmly attached to the shore – however, the journeys to which it invites its passengers are the most incredible ever.

On its pontoon, one discovers the garden’s pond, beginning an iterative mind journey. A journey unique to each passenger, that belongs only to us, and leads us to the most beautiful destination. For is it really necessary to travel physically if one can escape in their dreams, thoughts, and illusions?

The stone boat building is an ode to the immobile journey and to freedom regained. Such allegories helped Chinese scholars to escape from their uncomfortable universe. At the end of a quick walk in their garden, they could board their boat, to embark on infinite journeys. For the Chinese cultured man, this was the way to invite the freedom of the carefree fisherman in his life. Tossed by the waves of the river or the lake, in Chinese Daoism the fisherman represented the freest human being. Fishermen were often represented in Chinese paintings to punctuate waterscapes, adrift in their small skiff, floating far from this world of intrigue.

The symbolic of the ‘boat without moorings’ is, in my opinion, the most beautiful metaphor of the Chinese garden. It helps us find unlimited resources within ourselves, as infinite journeys become available. When one is in search of their own self, there is no need for artificial limits. Chinese gardens remind us that at the scale of the cosmos, human beings only have very small problems.

On the more practical side, of course Chinese scholars also liked to receive their friends aboard their stone boat for an evening of theatrical representations, for private meetings. The building could even evoke the famous ‘flower boats’ where real Chinese courtesans met their clients in Guangzhou (Canton).

The stone boat is arguably one of the most symbolic pavilions of Chinese imperial gardens – and culture. The last empress Dowager, Cixi, was heavily criticized for having spent fortunes to build the famous marble boat on the shore of artificial lake inside the Summer Palace in Beijing (Yuanmingyuan), after the destruction inflicted by the Europeans upon the older version (Yuanmingyuan).

This reconstruction seemed ill-advised in view of the immense needs of the country at that time. And yet, wasn’t it also a way for the empress Dowager to fight the overwhelming situation facing her with other weapons, cultural symbols intended to preserve the integrity of her people and culture? By pouring money into such a powerful symbol, perhaps she wanted to show the world that China would strive to helm the bar of its own boat and continue on its own journey, no matter what transitory turmoil was stirring the waves.

Text : Claudia Gillet-Meyer – Photos: Josepha Richard

More informations :

Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China