Can one imagine that at the very beginning of the 20th century, the Grand Canyon, this wonder that Mother Nature offered to the United States, was almost unknown to the pioneers of the West, only accessible by horse or by stagecoach?

It was in 1902 that the Grand Canyon Railway, a subsidiary of the Santa Fe Railway company, allowed visitors to come and admire this wonder. A unique set of circumstances occurred that only the American Wild West could bring about. The Santa Fe Railway was one of the largest railroad companies in the country and it was all the more successful economically when a man, a British native, added his elegance and hospitality to make the train ride a truly pleasant and appealing. This magician, named Fred Harvey, understood very quickly that hotels, restaurants and stores had to be associated with the train stops, but above all, he did it with good taste. This was the first opportunity for the Grand Canyon to show itself to the world.

Fred Harvey immediately imagined a luxury hotel, like a mountain chalet, built of logs and close to the train station that welcomed all the visitors dazzled by this monument of nature. Hotel El Tovar was for a long time considered one of the most expensive buildings of its kind, because no expense was spared to make its guest’s stay comfortable as well as unique. But Fred Harvey was not satisfied with only building a hotel. He was a visionary and foresaw the excitement that the Grand Canyon would bring. He thought of additional facilities and, to do this, he knew a talented architect whom he had already collaborated with on past projects. Her name was Mary Colter.

This extraordinary woman, born in Pittsburg in 1869, had studied design and architecture, a profession then restricted to men, and she was passionate about Native American art. At the Grand Canyon, Fred Harvey entrusted her with the realization of the first retail store in front of the El Tovar Hotel where Native American art would be highlighted to entice the passing tourists.

So presented, the business was a good commercial operation but the brilliant association of Fred Harvey and Mary Colter created a model for the preservation of the site.

While the hotel was being built of logs, Mary designed a house that would pay homage to the Hopi houses, the original inhabitants of the area. Made from local stone and wood, and featuring several traditional decks, the house was built by Hopi workers who brought their traditional skills to the table.

Inside, the Hopi House design combined Native American rooms with adobe walls and rustic Navajo rugs on the floor with a large Spanish-Mexican style room with a fireplace where items were sold. Several Native American artisans were demonstrating their craft, from basketry to weaving or jewelry. This was a great novelty for the time, and visitors were as surprised by the discovery of this indigenous culture that was unknown to them as by the scenery that the Grand Canyon offered outside.

From 1910 on, Mary Colter worked full time for Fred Harvey’s establishments as a design architect primarily for all his new hotels associated with the development of the railroad. It was at the Grand Canyon, however, that her association with Fred Harvey was, in my opinion, the most profound.

Within a few years, the development of tourism on the site was such that a first road was built towards the West of the South Rim of the Canyon in order to make it possible for the visitors to benefit from various points of view – one more spectacular than the others. This road, which is about 15 kilometers long, was named Hermit Road, and was to end at a point that would punctuate the route while allowing tourists to rest and have tea or refreshments.

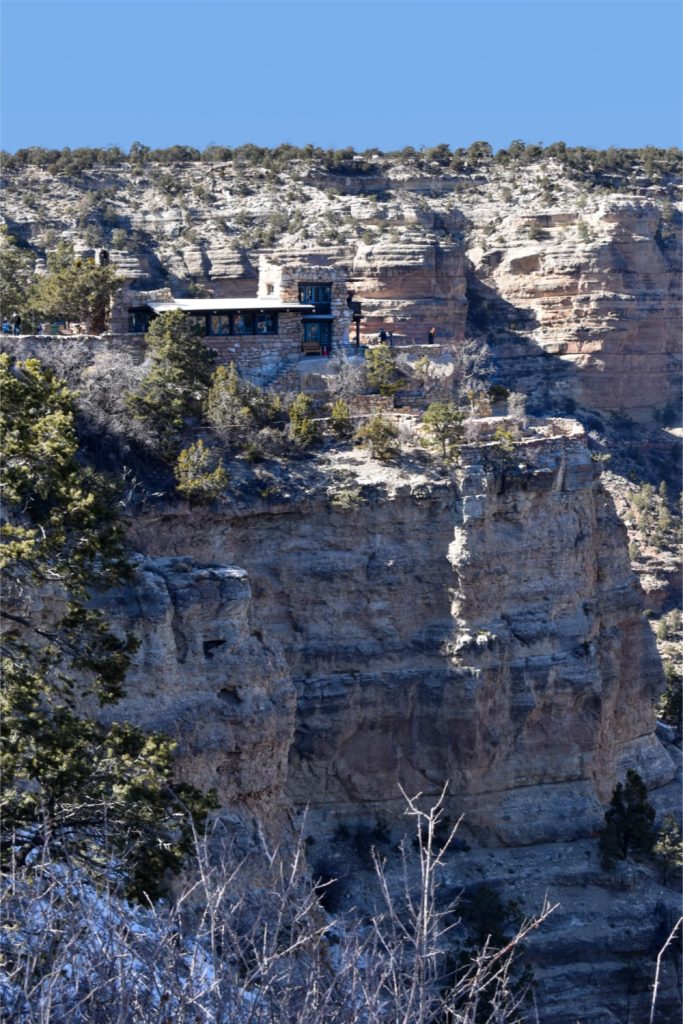

Mary Colter proposed a stone building, very close to the style of the natives of the region, able to match the landscape without ever disfiguring it. Above all, she wanted Hermit’s Rest to be so perfectly integrated that visitors would not be distracted by anything other than the natural appeal of the site.

When the place was opened in 1914, one of the railroad company members, faced with the rusticity of the building, said to Mary, “Why don’t you make it look a little better?” and she laughed and replied, “You can’t imagine how much it costs to make it look so old!” In fact, she had made a building that looked as if it had always belonged to the rocks it was leaning against.

A love affair was being born between the Grand Canyon and the architect. She understood that this giant had to be protected, now that the public was going to take it over and that it was essential to preserve its wild beauty.

Until 1933, as tourism developed, Mary designed new developments on the site with the same determination to maintain the integrity of the surrounding nature. She created a country hotel made of log cabins at the bottom of the Canyon called Phantom Ranch, another observation site called Lookout Studio, and the Bright Angel Lodge. Finally, she punctuated the second road built east of the South Rim with a tower called the Desert View Watchtower.

All of these constructions were inspired by the architect’s deep respect for the Grand Canyon. While they served commercial needs, they always had to blend in with nature and intrude on it as little as possible. Her style captured the essence of the past, whether it was the ancient habitats of the native people or those of the early pioneers.

In addition, the interiors were extremely meticulous; she thought through all the elements of the decor carefully, overseeing the execution in every detail. She was stubborn, demanding, always a perfectionist and determined, especially because she was evolving in a world of men where she had to make her ideas prevail and defend them to the end.

The Grand Canyon was declared a “National Park” by President Wilson in 1919 to protect its unique and spectacular landscape. Thanks to Mary Colter, the tone had been set. All of her achievements are still present on the site today. The three most emblematic places are those she designed to allow visitors to admire the Grand Canyon as a work of art spread out at their feet. They are free to enter and free to view.

But Hermit’s rest at the western end of the southern shore, Desert View at the eastern end and Lookout Studio in the middle are more than just viewpoints. They look like sentinels posed as watchmen, overseeing this immense dragon so majestic but so vulnerable as man is its worst predator. And in fact, a few dozen kilometers to the west, unscrupulous investors have built from 2004 a glass bridge in the shape of a horseshoe overhanging the precipice. This architectural feat of more than 30 million dollars is like a disparate wart, totally inappropriate to the place. Controversy is raging because the few minutes of thrill of walking above the abyss cost visitors a fortune.

Mary Colter must have anticipated this. By posting “her” guards along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, she has put its most beautiful part under her eternal protection. And we thank her warmly!

Text from Claudia Gillet-Meyer and photos from Régis Meyer.

MORE ABOUT :