The great international exhibitions were invented in Europe in the middle of the 19th century, in order to present to the public the technical and scientific progress of nations. In their path, other exhibitions were born, but today we forget to mention them, because they are no longer politically correct. I am referring to the “colonial exhibitions”. Within a few years from each other, London (1924-25), Seville (1929-30) and Paris (1931) carried out these crazy projects to celebrate the glory of the Empire or the Mother Country.

While England and France continued possession of their colonies when they launched the idea of these events. The end of the 19th century sounded the death knell of the Spanish conquest. The Kingdom of Spain was no longer and all of the American territories had emancipated themselves from its Hispanic tutelage.

So why such an exhibition in Spain, and why in Seville?

It should be remembered that Seville was the fourth largest city in Europe in the 16th century (after Paris, London and Naples). From its port on the Guadalquivir River, galleons left for the New World, returning loaded with gold from the Americas. This city, then rich, attracted bankers, merchants and artists from all over Europe as well as adventurers from around the world. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was only a provincial town, but it was still immensely symbolic. And it is precisely and entirely around the “symbol” that this exhibition called “Ibero-American” was imagined, whose host city could only be Seville.

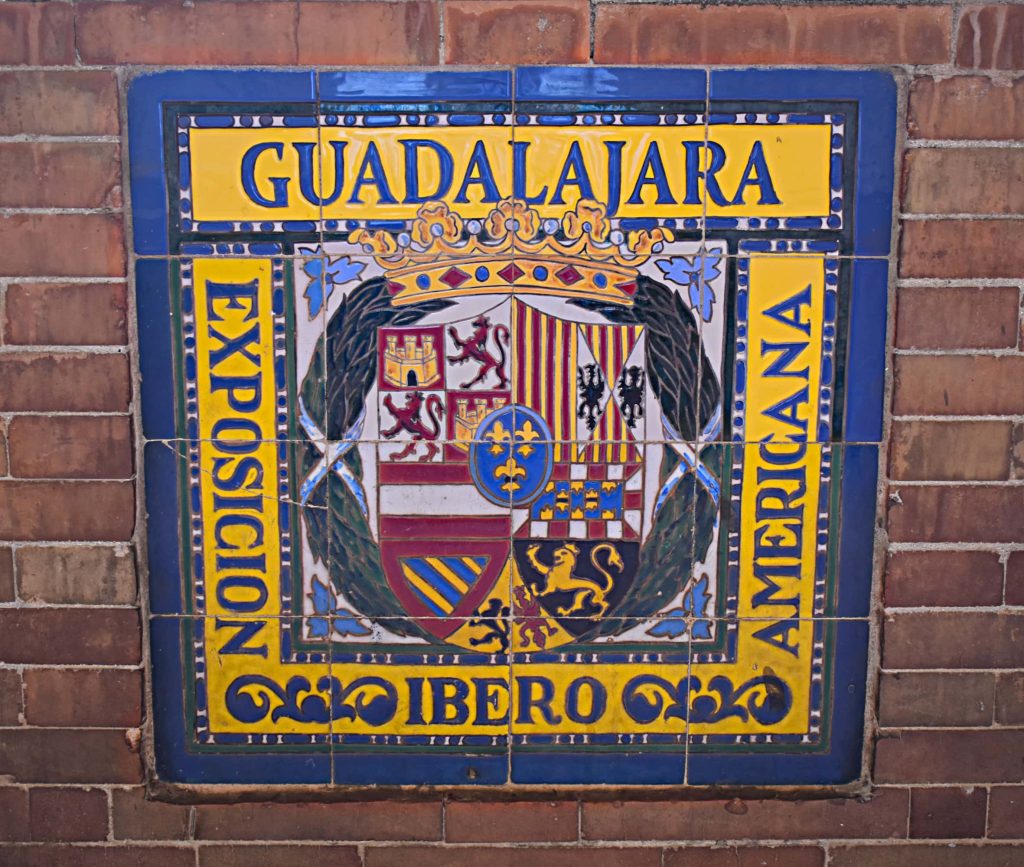

In fact, Spain was ruled by the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera and “this” explains “that”. Behind this exhibition, there was the idea of commemoration, of national identity, even nationalist, of a return to a glorious past “proving that the Spanish colonial heritage was also synonymous with progress”. The project was colossal and took nearly 30 years to complete, as it was interrupted by the First World War.

If analyzed critically, this exhibition may seem like a caricature in the way it invoked historical references, positioned the pavilions and named the spaces. Thus, the “Plaza de España” – the flagship monument of the exhibition, in reference to the nation then described as “Mother and Educator of Peoples” – and the “Plaza de las Americas” – that of the former colonies – were found on both sides of the park, connected by avenues bearing the names of … conquerors!

Considered more as a stepmother than as a protective mother, Spain had complicated relations with the American-Hispanic world and it is questionable whether such a spatial arrangement could really promote dialogue between peoples who had taken opposing opinions of historical events.

In short, the exhibition itself could be debatable, but like all such events, something interesting always remains, a remnant, a “pavilion” that has escaped destruction or has been consciously preserved. This is indeed the case with this ” Plaza de España “, which was erected as a monument to the glory of Spanish unitý under the aegis of the Catholic Monarchs against its American kingdom. Everything was thought of in a gigantic and symbolic way and it has been said that its building, erected in a hemicycle 170 meters in diameter and finished by two 80-meter high towers, was like a matron hugging her former Empire.

The base of the edifice is punctuated by 48 benches covered with tiles representing the Spanish provinces, and the river that winds through its middle, symbolizing the Guadalquivir, is crossed by four bridges dedicated to the kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Navarre and Leon.

Could it be more evocative?

Told like this, the monument could make you nauseous, but in fact, it is exactly the opposite.

Today, when we walk through this place, we totally forget all these references. They are forgotten or ignored, because beauty has erased the weight of the symbols of the past. I don’t know if the architecture is remarkable but it is certainly enchanting. Regardless of its representation, this square has come to exist on its own, thumbing its nose at all its sponsors.

It is elegant, be it a little haughty or detached, having completely emancipated itself from the role it was assigned in order to do as it pleases. Like a flamenco dancer, it lets the colors of its clothes twirl, throwing its arms in the blue sky of Seville to welcome the Sevillians and the other visitors without any distinction of culture, country or language.

It no longer seeks to demonstrate a vanished greatness within the narrow framework of a simple exhibition. It exists by itself.

Each time I rediscover it, I find its personality stronger, more endearing or friendly. It is almost alive, inhabited by a kind of humanity, the art of work having escaped its creators. Ironically, now that it has nothing left to prove, this square has established itself as one of the most majestic plazas in the world.

Text from Claudia Gillet-Meyer and Photos from Régis Meyer.