Il y a des histoires qui commencent là où elles ne devraient pas commencer. Question de principe. Ou de spirale. Celle qui nous fait mettre le doigt, le nez ou l’oreille là où il ne fallait pas. Là où tout va se dérouler dans un sens inverse de celui qui était prévu.

Cette histoire-là commence chez un bouquiniste.

Un excellent bouquiniste marseillais de la rue de Grignan ; homme adorable qui connaît ses livres et ses clients. Sa boutique est un antre du savoir et un boudoir de l’amitié.

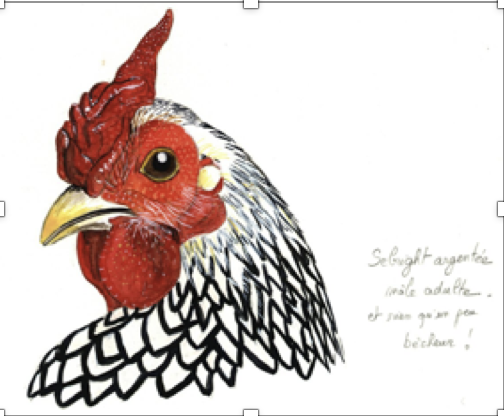

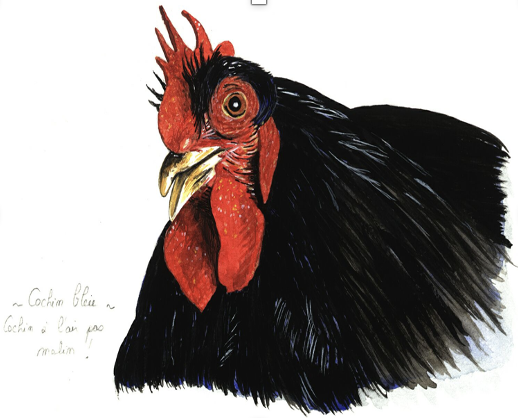

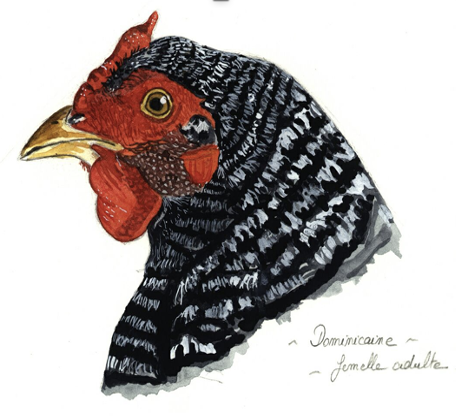

Aquarelles de Juliette Adrien

On y trouve de très beaux livres, des livres rares, des livres curieux, des livres insolites, des livres spécialisés et des livres distrayants. À l’image du propriétaire, homme de l’art et de la conversation, bon vivant et bon buveur, amateur de galéjades et de doctes histoires, truculent et chaleureux. Autant dire que j’aimais y venir. Et les nécessités de mon travail m’y conduisaient souvent car je savais que je trouverais toujours de quoi alimenter mes recherches.

Le grand intérêt de cette librairie est justement de se laisser porter par son éclectisme. Se balader dans les rayons « sérieux » quand les motifs professionnels l’exigent, puis se laisser guider par l’intuition vers des étagères aux livres plus marginaux où il est plaisant de trouver des histoires sur des sujets abracadabrants, traités cependant avec toute la rigueur qui leur sied.

C’est ainsi que mes doigts se baladaient sur les tranches de livres aux dimensions diverses et que ma tête se tordait sur le côté dès qu’une texture me plaisait où qu’un titre inhabituel m’interpellait. Voilà donc comment je tombe sur une édition de 1924, intitulée Toutes les poules et leurs variétés*.

Voilà aussi le vrai début de cette histoire.

Que peut-on faire d’un volume de 644 pages dédiées aux poules quand on habite en plein cœur de ville ? Rien. Absolument rien. Et c’est la raison pour laquelle je l’ai acheté.

Sur la couverture, en tissu grège, se trouve incrusté un médaillon dans lequel trône un profil de coq avec une crête phénoménale en éventail. L’animal est dessiné mais il a un regard si perçant et une allure si débonnaire qu’il met mal à l’aise. L’air de dire : « Cher futur lecteur, sachez que la poule n’est pas une dinde, ni le coq un dindon. » De quoi vous en imposer tout de suite et vous faire reculer si toutefois vous aviez une opinion ingrate ou peu flatteuse sur ces volatiles. N’ayant rien pour ou contre les poules, j’ai passé outre et j’ai ouvert l’imposant volume. Je l’ai d’abord feuilleté, pour être très honnête. Par curiosité. Ou par une tentation que je ne saurais nommer. La fameuse spirale qui nous fait mettre le nez où il ne devrait pas être. J’ai évidemment commencé par les images et … les illustrations m’ont époustouflée.

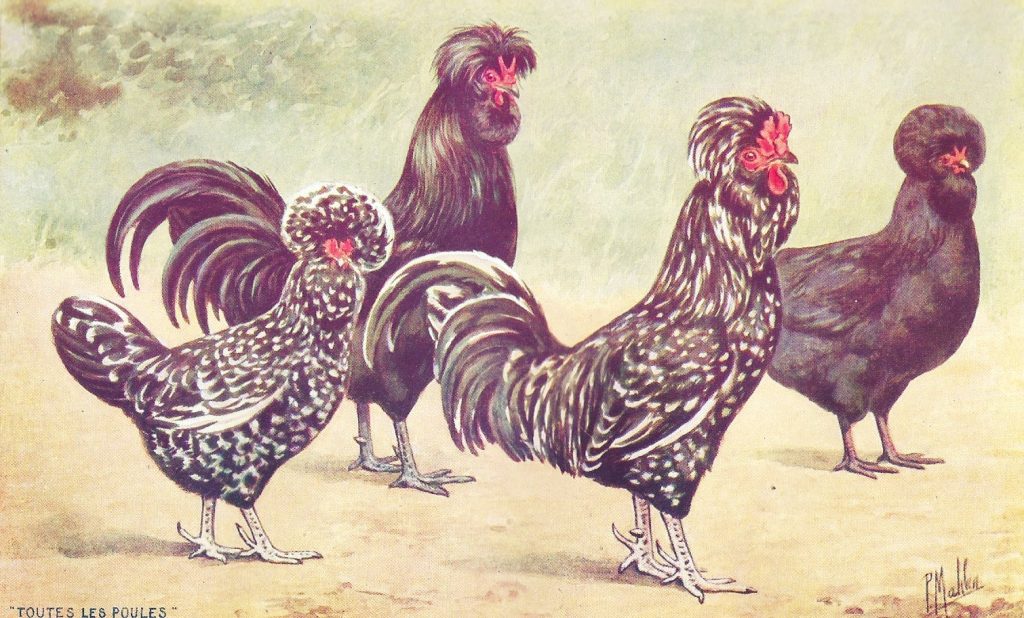

Des poules incroyables ! Ces planches peintes, magnifiques au demeurant, présentaient des poules venues d’un autre monde. J’ai d’abord cru à une blague. Ou bien à un livre de fiction sur « la poule idéale pour concours de beauté ». Un genre de délire émis par des savants fous, qui auraient croisé des oiseaux rares entre eux pour en faire des espèces curieuses. Mais, en revenant sur la première page, j’ai eu le bec cloué en lisant l’avertissement fait au lecteur et signé par l’honorable Comte Delamarre de Monchaux, correspondant de l’académie d’agriculture et Président de la Fédération nationale des sociétés d’aviculture, pour ne citer que deux de ses nombreux titres.

Donc, ces poules extravagantes existaient. Là, je dois dire que mon intérêt a redoublé et que j’ai étudié d’un plus près le texte.

Cet ouvrage est très, très sérieux. C’est même une thèse sur la poule. Et le coq. Il n’y est pas question de rigolade. Tout au contraire. Il s’agit de causer de choses très importantes entre personnes de bon entendement, qui savent de quoi il retourne.

« Les races gallines et leurs variétés sont différenciées par leurs caractères extérieurs. Les appellations usitées dans le monde avicole ne sont pas toujours d’une exactitude parfaite au point de vue de la zootechnie… » Qu’on se le dise !

La première phrase du premier chapitre ne prête pas à confusion. Si vous avez l’intention d’acheter et de lire un tel livre, c’est évidemment parce que vous en connaissez déjà un bout sur le sujet. Tout mon contraire. Je l’ai acheté et ma vie a basculé.

Pas tout de suite. Et en douceur, il faut dire.

Aquarelles de Juliette Adrien

D’abord, ce livre abscons est devenu mon livre de chevet. Je n’aurais pas cru m’amuser autant avec un ouvrage pareil. La thrombine des poules y était pour quelque chose. Un peu futile peut-être, comme première approche, mais je défie quiconque de rester indifférent devant le tableau récapitulant les diverses formes de crêtes. Les simples et les frisées. Les doubles, les droites, les grandes, les petites. La nature est une merveilleuse modiste ! Elle a fait aux poules et aux coqs, des couvre-chefs « Haute-Couture ». Une débauche d’imagination. De ces crêtes qui vous font dresser les cheveux sur la tête. Parce que la crête de base, toute bête, en éventail, qu’on voit partout sur un dessin de poule, c’est du vol manifeste d’information ! Il existe des dizaines et des dizaines de crêtes mille fois plus intéressantes. Celle qui se replie sur l’œil par exemple, et qui donne un air de gâcheuse. Celle qui est roulée comme une fraise pour l’habit d’Henri IV. Celle qui ressemble à un casque de coureur de bobsleigh. Celle qui a deux pics tels les cornes du diable. Celle qui a éclaté comme un pétard au-dessus de la tête, ou comme une bulle de malabar. Toutes ces crêtes bizarres autant qu’étranges sont inconnues au commun des mortels. Et c’est un tort.

Passé le divertissement facile de toutes les illustrations, planches, photographies (en noir et blanc), je me suis attaquée au texte. « Attaquer » est vraiment le mot qui convient.

Les 644 pages sont imprimées très serré, tout petit et sur deux colonnes. Comme quoi, il y a de quoi dire sur la poule.

Et, pas un seul plaisantin n’a écrit dans ce livre.

On y trouve le classement de toutes les races de poules, des sous-variétés, des nomenclatures, des standards, des monographies, de leurs qualités et de leurs exigences, de leur rendement, et j’en passe et des meilleures.

Normalement, ce genre de livre devient vite ennuyeux, par son côté technique et spécialisé. De celui-ci, au contraire, se dégage un je-ne-sais-quoi qui le rend attachant, poétique et drôle. Au second degré. Il est tellement sérieux et érudit qu’il en devient surréaliste et cocasse.

C’est la raison pour laquelle je suis passée du stade de passionnée à celui d’accroc.

J’ai adoré les conseils de préparation aux expositions, comme la technique de massage des crêtes retombantes de la poule bressane, destinée à les faire se plier d’une manière régulière. Ou le nettoyage des oreillons à l’eau tiède puis frotté avec un peu de vaseline pour leur donner une blancheur incomparable

Et que dire des altercations entre spécialistes de telle ou telle race, dont les discours aux comices agricoles sont reproduits avec toute la pompe qui leur convient.

J’ai appris que les poules avaient de drôles de personnalités et qu’il fallait en tenir compte avant de se lancer dans un élevage. Il y a les vives, alertes et vagabondes. De celles qui aiment la liberté. Les actives, les dociles, les sauvageonnes, les rustiques, les fragiles, les indépendantes, les maternelles, les fugueuses, les sociables. Qui l’eut cru ?

Je me suis transformée aussi en experte sur la taille et la couleur des œufs. Des mérites des gros jaunes ou de jaunes-orangés, des coquilles denses, solides ou fines, mouchetées ou virginales, des calibres exceptionnels.

Puis, j’ai plongé dans les délices de toutes ces chairs, juteuses, délicates, parfumées, au goût de noisette, à la texture incomparable.

Je suis restée médusée devant les portraits des présidents de sociétés avicoles, ces hommes aux moustaches fines, au port altier, les bras croisés sur leur poitrail dressé, tels des coqs, avec des petites lunettes cerclées, qui ressemblaient tous à des magistrats.

J’ai été tétanisée par les conseils stricts donnés aux éleveurs, qu’ils soient fermiers, paysans, amateurs, employés ou retraités.

Bref, je suis devenue une spécialiste à mon tour. Gonflée de tout ce savoir parfaitement inutile dans ma situation de citadine. D’autant que les seuls poulets que je pouvais voir, étaient tous ceux que mon livre haïssait. De ces poulets de batterie, à l’élevage incertain et industriel, à la race inconnue. Pire encore. Des hybrides américains, fabriqués par des laboratoires pour être gavés en 28 jours et prêts à la consommation.

Après m’être délectée de toutes ces races subtiles, créées au fil des siècles pour le plaisir des yeux et des papilles, j’ai trouvé l’univers actuel des gallinacés bien triste et monotone. Où donc se trouvaient ces poules fantastiques ?

Il fallait laisser le temps m’apportait sa réponse, car, comme toutes les histoires, celle-ci a ses rebondissements.

Quelques années plus tard, embarquée par les péripéties de la vie, je me suis retrouvée à la campagne. Non pas de passage comme une vacancière mais à y vivre vraiment. Dans une maison en haut d’une colline, avec des champs autour, et … les vestiges d’un magnifique poulailler !

Comme quoi, les histoires ont toutes un sens, quelque part, même lorsqu’elles commencent de manière tordue.

Le deuxième plongeon que j’ai fait dans mon livre, n’a plus été en eaux troubles. Contre toute attente, j’allais pouvoir passer du rêve à la réalité et ce livre devenait mon guide. Quelles races allais-je choisir pour peupler mon poulailler à étages ? Mon poulailler avec balcon et coursive. Mon poulailler avec sa mare devant. Mon poulailler avec des portes en bois dans lesquelles j’ai dessiné des cœurs que j’ai grillagés (pour éviter les fouines). Mon poulailler quatre étoiles, avec room-service.

J’ai couru les foires agricoles et j’y ai vu, de mes yeux-vu, les races inouïes décrites par Monsieur le Comte, en couleurs et en vrai, en chair et en os, en plumes et en crêtes, et en bec, et en pattes. Des poules de toutes les tailles, de toutes les nuances, de toutes les grosseurs avec des petites têtes dressées et un œil vif qui vous regarde de côté, plein d’interrogation.

J’ai fait tout ce que mon livre disait qu’il ne fallait pas faire. Je les ai mélangées. Impossible de me contenter d’une seule race. Je les voulais toutes. La grande Brahma avec des plumes aux pattes, la petite Padoue avec la huppe dans les yeux, la grosse Orpington qui se dandine, la fière Legbar, l’espiègle hollandaise en justaucorps, la blanche Sussex collet monté. J’ai rendu visite à des éleveurs qui m’ont toisée d’un air méprisant et à qui j’ai rabattu le caquet avec toute ma science de 1924. Je me suis bien gardée de leur dire que j’avais d’autres races que celle que je venais leur acheter au risque de passer pour une mécréante. Et encore moins de leur avouer que toutes mes poules avaient un nom. Ainsi que mes coqs. Car, en plus, j’ai plusieurs coqs, contrairement à toutes les lois du genre.

Tout cette petite communauté s’est installée dans ses appartements, en haut et en bas et j’ai découvert ce que mon livre ne disait pas : la magie et le plaisir d’avoir des poules (et des coqs !).

L’ouverture du poulailler le matin. Les quatre portes qui claquent au vent. Et les poules qui sortent. Celles qui s’éjectent comme des « fêlées, » comme si elles avaient un besoin urgent ou un œuf à délivrer en DHL. Celles qui font la grasse matinée et qui vous regardent, du fond de leur box, avec du sommeil dans l’œil, indignées d’un réveil aussi brutal. Celles qui volettent autour de vous, affamées. Celles qui s’éloignent à grands pas du poulailler, le bec au vent, dédaigneuses de vos graines, allant chercher le ver frais du petit matin. Et les coqs qui s’ébrouent et qui se la jouent, en roulant les mécaniques. Les concours de chant. Celui qui cocoricote aigu, celui qui n’y arrive pas et qui déraille à la fin du cri, celui qui nous casse les oreilles, celui qui se prend pour une publicité et qui s’égosille de profil, en ombre chinoise découpée sur le tas de paille, avec le lever de soleil en toile de fond.

Puis, la journée s’égrène et des groupes se forment, par quatre ou par neuf, ou par trois, ou tous ensemble, hors des limites du poulailler, en totale liberté ; ce petit monde part se promener pattes dessus, pattes dessous, en quête de tout ce qui pourrait être intéressant à becqueter. Un tableau de plumes éparses et multicolores sur fond de prairie. Du bucolique pur jus.

Et de me souvenir du regard de ce coq, sur la couverture de mon livre, qui me faisait savoir que la poule n’était pas une dinde.

La poule est un enchantement. Le coq aussi. Les voir vivre est un vrai bonheur.

Leur lancer du pain, assise sur les marches du perron et attendre que l’une d’elle s’en aperçoive. La voir débouler avec le feu aux fesses, négociant en dérapage le virage autour des glycines pour prendre les autres de vitesse car dès que ce premier signal est donné, c’est la cohue assurée.

Il y a Mina, la grosse Orpington, qui arrive en sautant d’une patte sur l’autre, projetant sa masse de plumes de gauche à droite dans un dangereux mouvement de tangage. Penny et Twiggy, les Sussex, mes deux gouvernantes anglaises, courent comme des dératées, en redressant leurs jupons. Charlie et Shiva, les Brahma descendants indiens, très dignes dans leurs pantalons bouffants, avancent avec des enjambées de mannequins qui marchent sur le fil du rasoir. Tosca et Aïda, les Padoues à la tignasse hirsute déambulent à tâtons, toujours une plume dans l’œil. Quant à Onyx la hollandaise dévergondée, Edelweiss, la nègre soie « chochotte », et Pétronille la délicate Batam de Pékin, elles sont de vraies flèches en mouvement. Elles se faufilent, ont une autorité hallucinante, passent entre les pattes des plus grandes. En dernier, se profilent la Faverolle, Éloïse, qui vient picorer dans mes mains en sortant son long cou d’autruche et Mahé, la cochinchinoise, qui ondule comme dans une chanson de Juliette Gréco. Pas question, dans ces conditions, d’abandonner les comptoirs de Chine…

Jardiner. Soulever la terre, enlever les mauvaises herbes. Dix minutes après, elles sont toutes autour à gratter avec moi, le derrière remonté, petits lancers rapides de pattes sur le côté, le regard soi-disant absent mais le coup de bec vif et précis dès qu’un ver apparaît.

Se mettre à midi sous un parasol allongée dans une chaise longue. Elles sont là, à côté, enfouies dans la terre, les ailes étendues sur le côté, dans une position de moribondes. Couchés côte à côte, races et sexes mélangés, abandonnés à la torpeur de la chaleur, on dirait un groupe de touristes sur une plage grecque.

Les coqs ne se battent pas entre eux. Il y a assez de poules pour tous, bien que Pétronille ait deux coqs rien que pour elle, qui ne la quittent jamais et semblent lui vouer une admiration sans borne. Ils partent tous les trois le matin et sont inséparables tout au long de la journée. Il paraît que ce n’est pas normal.

J’ai aussi des œufs multicolores, dont la coquille va du blanc pur au marron chocolat, en passant par toutes les nuances de rosé, crème, jaunâtre et je dois dire que je ne sais plus qui pond quoi.

D’ailleurs, quand le poulailler se transforme en maternité, c’est le branle-bas de combat. Génération Woodstock. Les poules couvent ensemble les œufs de leurs copines. On les voit monter peu à peu sur des tas d’œufs de plus en plus imposants et il faut en retirer quelques-uns au risque d’avoir un baby boom. À tour de rôle, elles vont boire et manger et font des couvées de garde. Parfois même un coq les aide et chauffe un peu les œufs pour les délasser. Personne ne me croit, mais c’est vrai.

Comme toutes les lignées royales, ces poules-là font beaucoup de bâtards, et les métissages sont souvent très réussis. À proscrire, selon mon livre.

Tout ce que je fais est interdit, de toutes façons, et j’imagine le Comte Delamarre de Monchaux froncer les sourcils, au fond de mon livre, et échanger des propos cinglants avec tous ses collègues zélés des club avicoles. Il y a du rififi dans mon bouquin. Ces gens-là sont outrés par cet élevage sauvage et indiscipliné. Je suis une lectrice indigne. Fustigée.

J’enfreins les règles. Je transgresse.

Mais je n’ai pas le cœur à construire un poulailler HLM. À parquer. À séparer. À isoler. Et encore moins à choisir.

Quand j’étais petite, j’aimais beaucoup une chanson qui disait :

Dans ma basse-cour il y a,

Des poules des coqs et des oies,

Il y a même des canards,

Qui barbotent dans la mare,

Et cot, cot, cot, codec

Et cot, cot, cot, codec

Rock and Roll des gallinacés.

Je dois dire que mes éleveurs de 1924 ne sont pas très « rock and roll ».

Que diraient-ils si, en plus, je leur avouais que ma chatte passe parfois la nuit dans le poulailler pour être la première à mater les souris qui viennent se gaver de graines au lever du jour ? Et que mon chien adore soulever le derrière des poules le matin pour me dénicher les œufs le premier ?

Et surtout, surtout, que je ne mange jamais ni mes coqs, ni mes poules ?

Vous me voyez poser un plat sur la table, dans lequel gît Lulu, Gertrude, ou Horace ?

J’aurais l’impression d’être devenue cannibale.

« Toutes les poules et leurs variétés » description, standard, points d’élevage, par BLANCHON et DELAMARRE DE MONCHAUX. 644 p. Librairie Agricole de la Maison Rustique. Paris 1924.

“Un magnifique ouvrage qui ne peut manquer de séduire les amateurs par sa présentation particulièrement soignée et la compétence des deux auteurs qui l’ont rédigé.

Plus de 300 races ou variétés y sont décrites par la plume et par l’image. Mais de plus les praticiens trouveront des chapitres dont ils bénéficieront grandement : chapitres sur la zootechnie des oiseaux, les croisements, la ponte, l’incubation, l’élevage, le logement des volailles. L’hygiène est les maladies, le noviciat avicole en France etc.

Les illustrations qui accompagnent le texte sont dues au crayon et au pinceau d’animalier de premier plan.

L’éditeur n’a rien négligé pour donner à ce volume l’attrait d’un luxe de bon aloi et une présentation commode pour le lecteur. Deux noms sont attachés à cette œuvre qui marquera dans les Annales de l’Aviculture : celui de M. H.-L.-A. BLANCHON qui fût arrêté par la mort dans ce travail de longue haleine, et celui du comte DELAMARRE de MONCHAUX qui l’a terminé. Président de la Fédération Nationale des Sociétés d’Aviculture, correspondant de l’Académie d’Agriculture, M. de MONCHAUX était particulièrement qualifié pour continuer et achever la tâche entreprise par le regretté BLANCHON.

Cette collaboration, fortuite, mais féconde, a donné les plus heureux résultats, dont se féliciteront tous les aviculteurs, qu’ils soient amateurs ou professionnels, et dont ils sont assurés de tirer un profit certain. »

EN SAVOIR PLUS:

http://histoire-agriculture-touraine.over-blog.com/2018/06/delamarre-de-monchaux.html